Singapore society has been shocked and horrified by the vicious and cruel abuse of 4-year-old Megan Khung by her mother (Foo Li Ping) and mother’s boyfriend (Wong Shi Xiang) over the course of 13 months, resulting in the death of the child. To conceal their crimes, they burned the girl’s body.

Although they were initially charged for murder, they pleaded guilty to reduced charges of child abuse, culpable homicide and disposal of a corpse. Wong additionally pleaded guilty to drug trafficking and drug abuse. Foo was sentenced to 19 years’ jail, while Wong received a sentence of 30 years’ jail.

Much anger and criticism has been directed towards Megan’s preschool (from which she was withdrawn prior to her death) and social services, for their perceived failures to take the necessary steps to intervene and address the abuse.

The Ministry of Social and Family Development (MSF) has planned a “further review” of the case, which will “cover the responses of all parties”.

At Cultivate, it is our hope that discourse around this topic can be fair and more constructive, with a view to strengthening our child protection ecosystem. Thus, in this article, we share some reflections on this horrific and tragic incident.

To be clear, the purpose of these reflections is to offer our thoughts on some ways that we can improve as a society. The aim of this article is not to pin the blame on anyone, apart from Foo, Wong and their friend Nouvelle (who was living with them and involved in the burning of Megan’s body), who deserve to be punished in accordance with the law.

1. Less finger-pointing?

A highly concerning aspect of the discourse following this tragic incident has been the level of blame attributed to the social service agency Beyond Social Services (BSS) and the preschool run by BSS – Healthy Start Child Development Centre (HSCDC) – from which Megan was withdrawn.

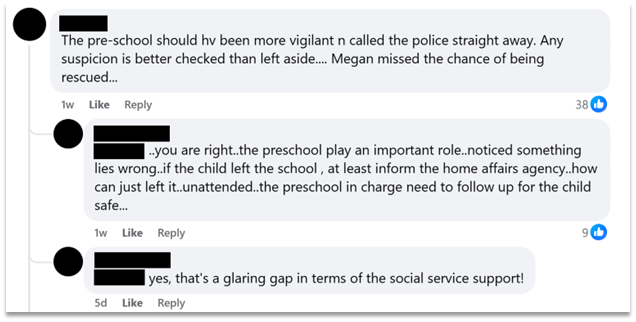

Consider the various comments on the Straits Times’ Facebook page, in response to the news.

There have been various comments blaming the preschool as well as social services for their perceived failures in their responses, such as the following:

Part of the issue may arise from the way that the matter was reported. The Straits Times had reported:

Between late February and early March 2019, the couple would cane Megan when she urinated on the bed and sofa.

Staff at the girl’s pre-school noticed bruises on her face, arms and feet. They told the couple that any abuse would be referred to the Ministry of Social and Family Development.

On Sept 17, 2019, Foo withdrew Megan from pre-school.

The way the matter had been reported left it unclear as to when the preschool staff issued their warning, and could give the impression that Megan was withdrawn immediately after the warning. In fact, this warning was issued on 22 March 2019, and there was a gap of around six months before Megan was withdrawn from the preschool. During those six months, there were reportedly no signs of injury.

In reports, CNA spoke of “lapses” in Singapore’s child protection services, “such as inadequate reporting and intervention”, which “led to the death” of Megan Khung.

Reporting on a press statement issued by the Ministry of Social and Family Development (MSF), which was aimed at strengthening the child protection ecosystem, the Straits Times drew from one paragraph within the 12-paragraph statement and headlined it “Info from Megan Khung’s pre-school gave no reason for ECDA to suspect girl’s abuse: MSF”.

Further queries and responses between Straits Times and MSF only intensified the criticism against BSS, stating BSS’s report of April 2019 “did not fully describe the severity of the injuries, as compared to the evidence presented in the court documents”. MSF added that the preschool and social service agency should have used the screening and reporting guides relating to child abuse management, and should have reported more decisively to Child Protection Services.

The intensity of the criticism directed against BSS is troubling, since – in the words of the High Court – the physical abuse of Megan “escalated” after September 2019. The child abuse offences for which Foo and Wong were charged and pleaded guilty took place between January and February 2020. These all took place after the preschool staff spotted the cane marks, warned Foo and Wong, and reported the matter.

It also risks losing sight of the fact that the blame falls squarely on the abusers who caused Megan’s death.

A better perspective is that of the Singapore Children’s Society, which said that it was “a collective failure of the system” that led to Megan’s death. In this regard, MSF has since clarified that its statements were not intended to “[imply] that certain parties could have done more to avoid the tragic death of Megan Khung”.

2. Appreciating the nuances of intergenerational relationships

Next, a better understanding of intergenerational relationships could help in preventing child abuse.

Following the initial incidents of abuse in February and March 2019, Megan’s grandmother was named the trusted caregiver under a Temporary Care Plan, and Megan was placed under her care following suspicions of abuse.

However, after Megan was withdrawn from preschool, the grandmother was reportedly hesitant to file a police report, “fearing that it would result in her being cut off from staying in touch with her granddaughter”. Nevertheless, the caseworkers from BSS continued their follow-up through the grandmother.

With deeper insights and appreciation of the complexities, dynamics and dilemmas of intergenerational relationships, these developments should raise alarm.

Parents and grandparents do not have an equal relationship towards children. Under Singapore law, parents are recognised as having primary responsibility over their children. Unless a grandparent is legally recognised as a guardian of the child, a grandparent’s legal rights over a child are very limited.

This legal position is also reflected in our social norms. Singaporean grandparents generally adopt a stance of “non-interference”, deferring to their adult children in parenting decisions for the sake of family harmony or even the opportunity to interact with their grandchild. Instead, grandparents tend to see themselves as playing a supportive role.

A better understanding of grandparents’ limitations would help to trigger swifter action in the future.

3. Wider ecosystem

Finally, we need to think about some aspects of the wider ecosystem that contributed directly or indirectly to the fatal abuse.

Drug abuse was part of the wider context in which the abuse occurred. All three adults – Wong, Foo and Nouvelle – were meeting to consume drugs on the fateful night that Wong punched Megan in the stomach. When Megan became unresponsive, they took turns to blow drug fumes into her mouth to try to revive her.

Foo did not call for an ambulance for fear that her drug use and abuse of Megan would be discovered. The same applied for Wong, who feared that removing a defibrillator would trigger alarms and lead the authorities to Megan.

It is well-known that Singapore takes a tough stance against drugs. This tragic incident is a stark reminder of the various indirect consequences of drug abuse and drug trafficking, where a group of adults irresponsibly put their own drug consumption pleasures (and fears of getting caught) above the interests of a vulnerable child.

Another important part of the wider circumstances that enabled the abuse was the breakdown of the marital relationship between Megan’s biological parents, and the entry of Wong into her mother’s life as her live-in boyfriend.

As studies have clearly and consistently shown, a biological parent’s unmarried partner (such as a mother’s boyfriend) poses a higher risk of abuse towards children.

This case illustrates the point, as Wong is undoubtedly the worst offender here. He abused and trafficked drugs, and was responsible for the most vicious and violent abuse inflicted on Megan, ultimately causing her death. He seemed to have a very harmful influence on Foo as well, teaching her how to inflict pain on Megan without leaving visible marks or injuries.

A deeply regrettable aspect of this case was how Foo repeatedly covered up for Wong, lying to the preschool about how Wong had hit Megan, ignored and even participated in the abuse, and finally conspired with Wong to dispose of Megan’s body after she was abused to death.

On the other hand, it was Megan’s biological father Khung Wei Nan who lodged the police report in July 2020 concerning Megan’s whereabouts. Sadly, this was already four months after her death.

Seeking a constructive way forward

Every child abused is one child too many. When it results in the death of the child, it should rightly prompt deep soul-searching throughout society.

We support the recommendations by the Singapore Children’s Society to enhance child protection within the preschool sector, namely:

- For all preschool educators and their management, whether pre-service or in-service, to receive basic training in child protection and to attend refresher courses periodically; and

- To appoint “Child Safety Officers” who take ownership of, and are proficient in managing child protection concerns within each preschool centre.

In addition to the above, we recommend the following:

- Building strong families. The truth is that, when the primary institution for children – their family – breaks down, all other institutions have to work doubly hard to fill the gap. Thus, the most upstream way of protecting children is to build strong marriages and families. These include having strong family commitment between husband and wife, and parents and children, and working to prevent or mitigate the consequences of family breakdown.

- Public education on child abuse. Too often, there is a fear of reporting on child abuse due to the fear of damaging one’s relationship with the suspected abuser. As this case also shows, there is an unfortunate tendency for some parents to turn a blind eye to child abuse (or even cover up and become complicit in it). There needs to be stronger public education to help people realise that abuse is not love, and it is not a loving thing to ignore or cover up for an abusive spouse or romantic partner. The message should be sent to parents – regardless of marital status – to place the best interests of their children first, and to proactively remove them from situations where they are at risk of physical or sexual violence.

- Risk factors in child abuse. Child abuse reporting and response protocols should clearly note and recognise risk factors such as substance abuse (e.g. drugs or alcohol) and family background (e.g. presence of an unmarried boyfriend/girlfriend of the parent, especially one who is co-residing with the child). If there are many risk factors involved, these should justify swifter intervention.

- Complexities of grandparents as caregivers. There is no doubt that many grandparents deeply love and treasure their grandchildren, and it is good to involve grandparents in a holistic effort to protect children from abuse. At the same time, a sound understanding of the complexities, dynamics and dilemmas of intergenerational relationships (including the inequality of position of grandparents as compared to parents) requires social services and Child Protection Services to intervene more swiftly in the event an abusive parent cuts off contact. If necessary, this requires bypassing grandparents’ hesitation to report on their adult children.

Children are the most vulnerable among us and deserve our utmost protection. For the sake of the many children who may be at risk of abuse, we owe a moral duty to do better and be better as a society.