“Couples in an unhappy marriage should divorce and move on. It is better for everyone, including the children.”

We hear this view quite often these days. During the 2022 Parliamentary debates over the introduction of “divorce by mutual agreement” (DMA), a number of Members of Parliament made arguments to this effect. But are they right?

Not necessarily so, according to Paul R. Amato, a professor who has studied this issue for a long time. Amato is currently Emeritus Professor of Family Sociology and Demography at Pennsylvania State University, having obtained numerous awards over time for his work.

In his view, there are couples in “good enough” marriages that are better off staying together and reconciling, as this is better for children in the long term.

“Good Enough” Marriages

“Good enough” marriages from a child’s perspective, as Paul R. Amato defined in a 2001 law journal article, are “low discord marriages” or marriages where there is a low level of conflict between parents.

Divorce is a sensitive topic, and there are diverse views on the issue, including in Singapore.

Amato is aware of the divergence in views.

On one hand, he notes that people with “conservative political and religious convictions” argue that “the breakdown of the family is the root cause of most social problems, such as poverty, crime, and drug use”, and believe that “the family is declining”.

On the other hand, are the “liberal and feminist perspectives” with “a more tolerant view of divorce”, who believe that “the family is as strong as ever, only more diverse”.

Describing his view as a “third view”, Amato recognises some truth in both the “liberal” and “conservative” views on divorce, while seeing each as a “one-sided simplification of reality”. He takes a child-centric view on the issue of divorce, focusing on long-term benefits and harm to children:

For some children, divorce is a relief from an aversive, dysfunctional home environment; however, for other children, divorce is the beginning of a downward spiral that can last a lifetime. Correspondingly, some marriages cannot be salvaged, and ending them expeditiously is the best outcome for all concerned. But other unstable marriages – marriages that are “good enough” from a child’s perspective – can be salvaged, and finding ways to help these parents stay together promotes children’s best interests. It is this third view, I believe, that best fits the accumulated research evidence…

“Good enough marriages” – How Good Are They?

Paul R. Amato has been studying the topic of marriage and divorce for around four decades, if not more.

In his 2001 article on “Good Enough Marriages“, he took evidence from a longitudinal study in the United States that had been ongoing since 1980, named “Marital Instability Over the Life Course”. There were approximately 2,000 married individuals who were interviewed over the telephone between 1980 and 2000. Telephone interviews were conducted with 691 young adult offspring from these marriages in 1992 and 1997.

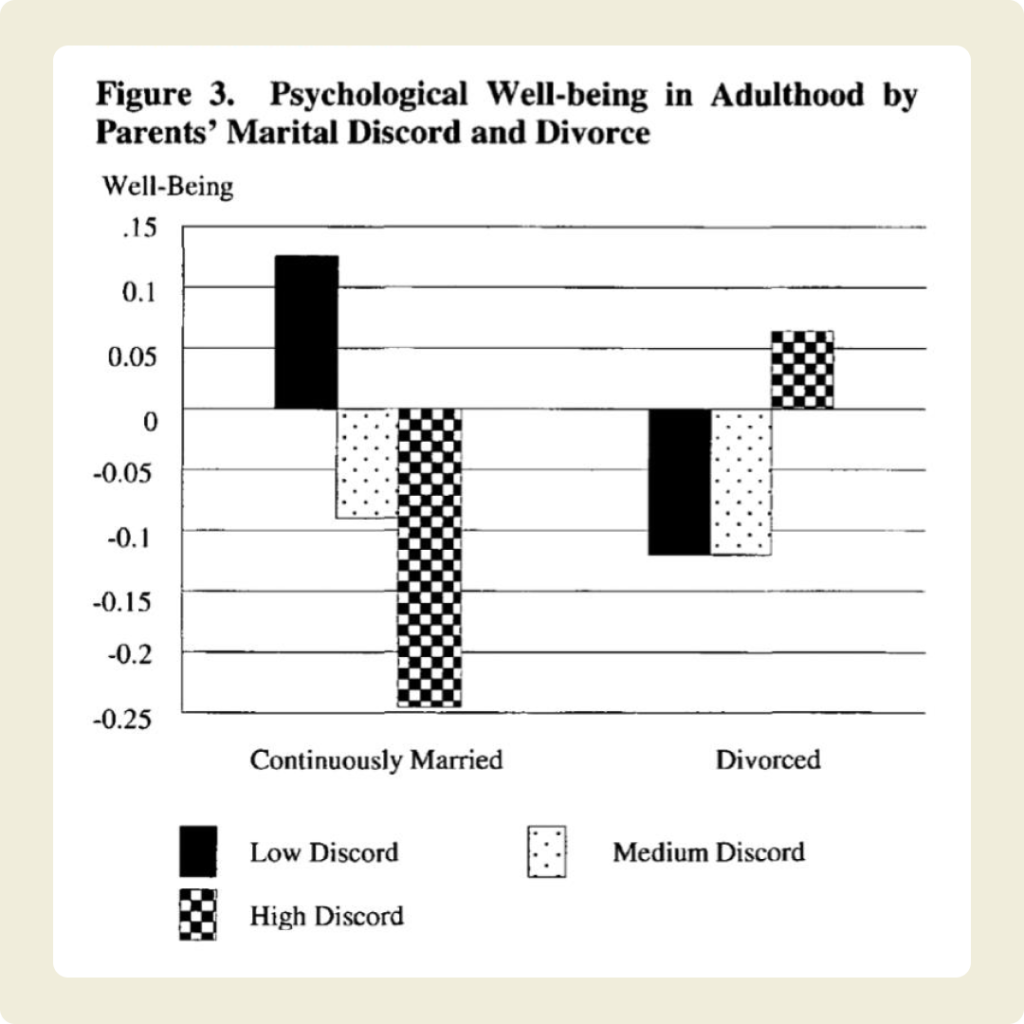

147 of these children experienced a parental divorce, and Amato had data on the quality of their parents’ marriage and family life prior to divorce for 93 of these children. He measured their psychological well-being in adulthood based on four measures: life satisfaction, psychological distress, self-esteem and overall happiness.

Here are the results of the psychological well-being of these young adults, based on their parents’ marital status and level of marital discord:

From these results, Amato argues that “when parents had a level of discord that placed their children at risk, divorce appeared to be in children’s long-term best interest” (compare the two checkered bars). On the other hand, “when parents had a level of discord that placed their children at little or no risk, divorce appeared to be contrary to children’s long-term best interest” (compared the two black bars).

In another 2001 article co-authored with Alan Booth, the authors found that dissolution of low-conflict marriages was associated with lower quality of children’s intimate relationships, social support from friends and relatives, and general psychological well-being.

Seeing from the Child’s Perspective

What explains these results?

Amato explains that children in high-conflict marriages find family life to be stressful, and “may even welcome a parental separation”. He adds that “If divorce removes children from a dysfunctional, stressful, and perhaps violent home environment, then it should benefit them in the long run.”

However, the situation is different for low-conflict marriages. Amato invites readers to consider a family where parents rarely argue in front of the children. “Parents may feel bored, fearful that life is passing them by, and concerned that the marriage is no longer helping them to develop their full potential as individuals.” As a result, one or both spouses “may decide to leave the relationship to find greater happiness with another partner”.

Although the scenario may “seem reasonable to a parent”, Amato explains that a child may interpret the situation very differently:

To begin with, the separation is likely to be an unexpected and inexplicable event. Most children will not see it coming. Moreover, children, generally do not care whether their parents are self-actualized or are suffering a mid-life crisis. Children care about frequent and warm contact with both parents, along with predictable family and neighborhood routines. When these “good enough” marriages end in divorce, children experience a variety of stressful circumstances-such as a decline in access to one parent, a drop in standard of living, the introduction of parents’ new partners into the household, and moving to a new neighborhood or city – with few or no compensating advantages. These divorces also are likely to affect children’s understanding of marital commitment, fidelity, and the long-term dependability of intimate relationships. Under these circumstances, it is not surprising that divorce increases the risk of long-term problems for children.

Thus, Amato concludes by voicing his concern that “the divorce rate is too high these days, and that many children would be better off if their parents remained together.”

What Does it Mean for Us in Singapore?

Over the past 10 years (since 2014), there have been around slightly more than 7,000 divorces per year on average. This is much higher compared to a few decades ago. For example, there were 1,551 divorces in 1980, 3,150 divorces in 1990, and 4,920 divorces in 2000.

In 2022, the Singapore Parliament passed the Women’s Charter (Amendment) Act 2022, which introduced “divorce by mutual agreement” (DMA). In Parliament, the Government stressed that DMA was “different” from the type of “no-fault” divorce in other jurisdictions where parties are not required to take responsibility for the breakdown of the marriage. It added that “[all] safeguards of the divorce framework today will continue to apply”, including the three-year time bar on filing for divorce and the three-month period before the divorce is finalised.

Under this amendment, divorce can be granted if the court is satisfied that the marriage has irretrievably broken down and it is “just and reasonable to grant the divorce, having regard to all relevant circumstances”, including the conduct of the parties and how a divorce would affect the parties and any child of the marriage.

During consultation, differing views were expressed. Some felt that the option would be beneficial to the family unit, provided that safeguards to prevent abuse are in place, while others were appalled by the proposal, expressing that the current laws are premised on the notion of preserving marriages and encouraging reconciliation.

To-date, the DMA amendment has not yet come into effect.

Currently, divorce can be granted if a marriage has “irretrievably broken down”. This is provable by the following “facts”:

- If a spouse has committed adultery and the other spouse finds it intolerable to live with that person.

- One spouse has behaved in such a way that the other spouse cannot reasonably be expected to live with that person.

- One spouse has deserted the other spouse for a continuous period of at least 2 years.

- The spouses have lived apart for a continuous period of at least 3 years and there is consent to a judgment being granted.

- The spouses have lived apart for a continuous period of at least 4 years.

Amato’s research, in our view, shows that there is a need to reconsider divorce, both in law and in practice, so that more “good enough” marriages (or low conflict marriages) can be saved and children’s long-term welfare can be better protected. As a start, perhaps our legal system should make more effort to encourage divorcing couples (especially those in low-conflict marriages) to consider the impact of divorce on their children, and to make more efforts at reconciliation. While in many cases, couples who have engaged lawyers have found themselves at the end of the road, there are also many cases where couples have not exhausted all means to save their relationship, and the legal system should be oriented towards facilitating these couples’ relationships, especially when they have children.

For parents who may or may not have sought couple therapy before starting legal proceedings, some level of mandated counselling currently comes into play only at the mediation stage, after divorce papers have been filed. This means the session already takes place within the context of legal proceedings, which are usually set on a certain course within the context of an adversarial system, where resources are limited, and there are competing tensions of justice and efficiency – all of which will affect the efficacy of such counselling. The goal of such a counselling session is to “resolve disagreement”, and does not prioritise efforts at reconciliation.

Ultimately, it is still more important for community and social support at the more upstream levels to also be aimed at reducing conflict within marriages, and providing resources to help parents make better decisions for the sake of their marriage and children.