In the dead of night, a woman walks furtively to a wrought iron gate at the corner of Victoria Street and Bras Basah Road. She leaves a baby swaddled in rags at the threshold of the gate, rings the bell, and leaves after saying her final goodbyes.

An European nun in a black habit opens a crack in the gate, reaches out and picks up the little baby. Closing the gate behind her, she bathes, clothes and feeds the child, then places the child in a cot alongside many other children who have been similarly abandoned by their desperate parents.

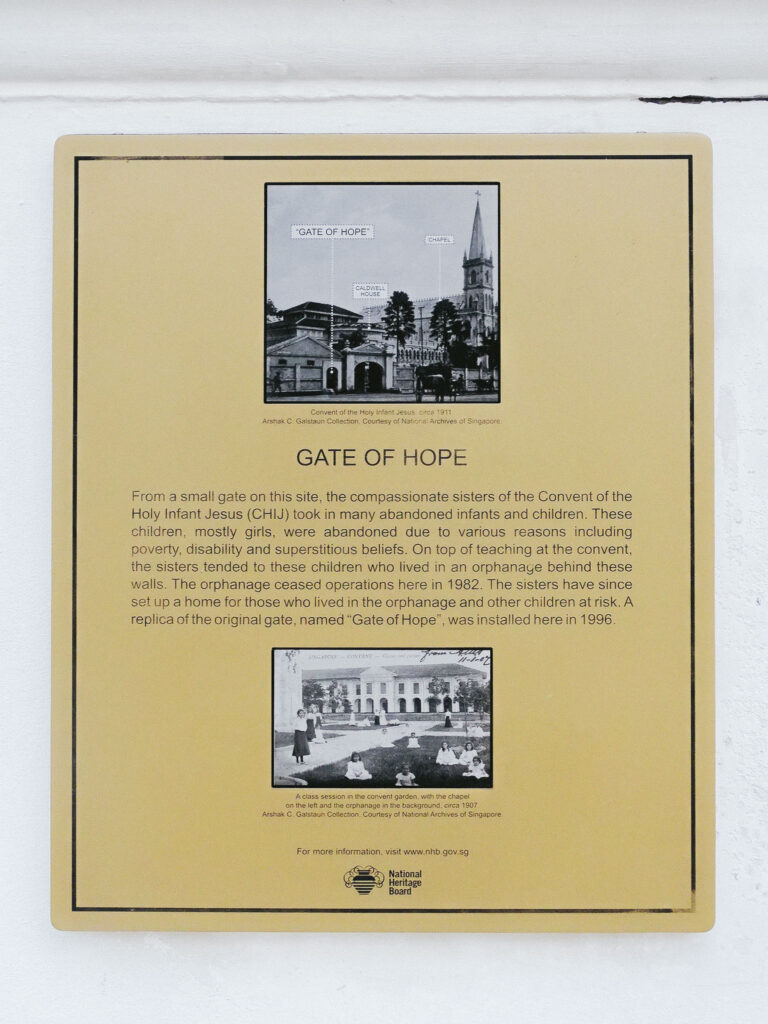

This was a familiar sight for a long time in pre-Independence Singapore. This “Gate of Hope” was the entrance to the orphanage and home for abandoned babies run by the Infant Jesus Sisters, a group of Catholic nuns. It was located at the Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus (CHIJ), popularly known then as “Town Convent”.

Conditions were tough in the early years of Singapore. It is estimated that Singapore’s infant mortality rate was around 99 per 1,000 live births in 1949.

Due to harsh socioeconomic conditions then, parents would sometimes abandon their children. Particularly vulnerable were children from poor and large families, or those who were born out of wedlock, sick, or had disabilities or deformities. Girls were more likely to be abandoned than boys, especially girls born in Year of the Tiger in the Chinese Zodiac, which was perceived to be inauspicious. Due to their poor state of health, not all children survived.

A Straits Times journalist who visited the convent in 1950 was “appalled” that “such small children should have to suffer so much”. He wrote about a baby named Rosa, who was born with only one hand. Her parents took her to the convent because they were superstitious, and believed her birth condition was a bad omen.

The story of the orphanage and home for abandoned babies is not only a compelling one, but holds many important lessons for us today.

Compassion, despite difficult circumstances

Town Convent was founded by Mother St Mathilde, who was born in France and came to Singapore in 1853. She was known to be a good teacher, and had wished for a long time to be a missionary in the East.

From this began the mission of profound compassion and care for the most vulnerable, even amid the most difficult circumstances.

Ever since Town Convent was established in 1854 along with its orphanage, people began to leave babies wrapped in rags and newspapers at its gates. In 1892, there were around 200 children, and the figure increased to around 400 in 1936.

Perhaps the most extreme circumstances occurred during the Second World War and the Japanese Occupation. During this time, orphans continued to be brought to the convent, especially girls with disabilities. However, the Sisters could not receive all of them due to limited resources.

In 1943, the Japanese deported around 40 of the nuns, many orphans and some teachers to Bahau (a place in Negeri Sembilan, modern-day Malaysia). With only a few flimsy huts in a thick jungle, the Sisters had to grow their own food and dig wells using makeshift tools. Unprotected from the elements and pests, a number of the internees died. When the war ended in 1945, survivors were repatriated back to Singapore.

All this time, the work of providing care for the children continued, into the period of post-war recovery. In 1946, there were four to five babies arriving every day.

Lessons from the Sisters

The deeds of the Infant Jesus Sisters throughout the years teach a number of important lessons.

The first and most important lesson is the intrinsic value of all children, regardless of their sex, appearances or abilities, circumstances of birth, or other personal characteristics. Everyone deserves dignity in life. Children received at the orphanage were from among the poorest backgrounds in society. Many came with no identification, and were given names by the Sisters. Those who were too frail and did not survive were christened and buried.

The second lesson is the dignifying value of education and gainful work. The children entered the convent school and received a free education. While some completed secondary education, most left after primary school and were taught vocational and domestic skills. Some moved out of the premises after getting married or after securing employment.

Thirdly, as the old adage goes, it takes a village to raise a child. The Sisters involved students who were studying at Town Convent in visits to the “baby house”, where the students would give the children gifts and treats, and even play with the babies. The students also raised funds in aid of the abandoned babies during their annual school fairs and by selling flags.

Finally, it is essential to support and empower families, since families remain the primary and natural source of support and care for children. As the number of abandoned babies decreased with improvements in standard of living, declining to around 50 in 1968, the Sisters began to pivot their model of care.

While the Sisters did their best to provide a family-like setting, such as establishing a Girls’ Town in Chestnut Drive in 1968 where girls managed their own domestic matters, the Sisters eventually realised that they could not fully recreate family life.

In 1980, they opened a residential centre in Clementi in order to provide a “more congenial, non-institutionalised environment for children to grow up among normal healthy families and to be involved in the community life”. The aim was to progressively move a child from residential care, to day care, and then to independence.

A society where children are valued

With Singapore’s development from Third World to First, the dire socioeconomic circumstances in Singapore’s early days are – thankfully – a thing of the past. In 1983, the orphanage closed when Town Convent moved out of Victoria Street.

Today, a replica of the original “Gate of Hope” stands at a corner of CHIJMES, sending a poignant reminder about the humane values for which it continues to represent today.

In 2015, when it was suggested in Parliament to establish “baby drop boxes”, the Government rejected the idea, citing “the downside of encouraging baby abandonment”. Instead, the Government explained that its focus was on ensuring a range of support services for expectant mothers who may be facing distress, and to protect the safety of both mother and baby.

It is said that “the true measure of any society can be found in how it treats its most vulnerable members”.

Today, the story behind the “Gate of Hope” reminds us of the deep values of compassion and self-sacrifice. It demonstrates how adults must do the difficult things in life so that children can thrive.

A society where every child is valued for who they are and given the best opportunity they can to flourish is something to be constantly cherished, cultivated and reinforced.

Every child is precious. Let’s treasure all the children in our midst, no matter their background or circumstances.