“The adoption court has seen time and again the deep, almost abstruse desire of adopted children to seek the face of their biological parents in an effort to find themselves.”

District Judge Shobha G. Nair

“Who am I? Where did I come from?”

All of us are familiar with deep and profound questions like these, whether because we have wrestled with them ourselves, or have heard of others who wrestle with such questions. This desire to know one’s identity and origin is something that perhaps all of us grapple with at some level.

For those who have been adopted as children, a big part of that search involves trying to find one’s biological or birth parents, as District Judge Shobha G. Nair alluded to this in a 2018 local court case quoted above.

The Right to Know One’s Natural Parents

An important legal case on this topic arose in the late 1980s, when 34 year-old architect Melati bte Haji Salleh embarked on such a quest to learn more about her birth parents, after finding out that she was adopted.

She believed that she was Chinese in ethnic origin, although her legal parents were Malay, and hoped to provide for her natural parents in her will. However, she did not want to ask her adopted parents about her natural parents, as she did not wish to hurt them in their old age.

Instead, she asked to inspect the defunct Adoption of Children Register and to make copies of documents relating to her adoption, including her original birth certificate.

When the Registrar-General refused permission, she applied to the High Court.

In a 1989 decision, Justice Chan Sek Keong (who would later become Singapore’s Chief Justice from 2006 to 2012), granted her the right to inspect the Register.

He traced the history of certain amendments to the Adoption of Children Act, which stopped revealing the fact of adoption in an adopted child’s birth certificate. However, the judge remarked that one “can never conceal” an inter-racial adoption “in a multi-racial society like Singapore”, citing the case before him.

In Justice Chan’s opinion, “it is only morally right that an adopted child in such a position should be granted the right to know who his or her natural parents are”, in the absence of public interest against disclosure.

He cited a further public interest reason why she should be allowed her request: Preventing her from entering an incestuous marriage, which is prohibited under the Women’s Charter.

Finding that the Registrar-General reached the wrong decision in refusing Ms Melati’s request, Justice Chan granted her request to inspect the Register.

This decision is consistent with international human rights law, since Article 7(1) of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) states that: “The child shall be registered immediately after birth and shall have the right from birth to a name, the right to acquire a nationality and, as far as possible, the right to know and be cared for by his or her parents.” (emphasis added)

In 1995, Singapore signed and became a party to the CRC, which to-date is the most widely ratified human rights treaty in world history.

Searching for One’s Parents

Like Melati bte Haji Salleh, there are many others who have gone in search of their birth parents. Some of these stories have been publicly documented by the Crime Library Singapore, Straits Times, New Paper and other sources.

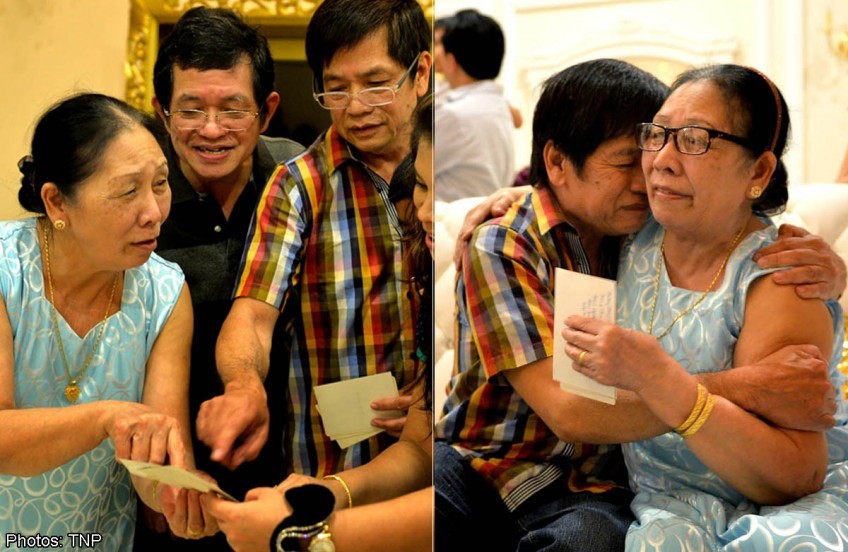

One interesting story is that of Madam Thanapakiam. Her birth parents were born in China, and she was ethnically Chinese. She was put up for adoption because her father had been captured during the Japanese Occupation, and her family was poor. She was adopted by an Indian family and considers Tamil as a language close to her heart.

Even though she was “the apple of her (adoptive) mother’s eye”, she wished to reconnect with her biological family, telling the reporter: “Everybody has a mother, and my greatest desire is to see the lady who gave birth to me.”

With the help of the New Paper, she was reconnected with her biological brothers, who surprised their long-lost sister who travelled to her house for the reunion. Unfortunately, Madam Thanapakiam did not have an opportunity to meet her birth mother, as she had died 13 years ago at the age of 91.

Going on a similar journey was Dollar Christine Abbott, who was born in Singapore to a then 22-year-old single mother, Esther Mary Glynn.

Ms Glynn made headlines more than half a century ago in a 1958 Straits Times report, because she put up an advertisement which read: “Baby girl – 66 days old of mixed English and Siamese parentage, for adoption to suitable couple.” She told reporters at the time: “I think this is the best way to find a married couple who will really love her and give her a good home.”

Ms Abbott was adopted by a British couple who moved back from Singapore to England, where she grew up. Ms Abbott told the Straits Times: “I realised then, what a big thing (my birth mother) did for me… I wanted to tell her I’ve had a nice life, and I’m glad she did what she did.”

Crime Library Singapore has featured numerous appeals by and on behalf of individuals who were adopted. One woman said that she was “earnestly looking to reunite with (her biological parents)”, and a man wanted to know his biological parents because “(he has) deeply desired this all my life to know who I really am.”

One woman shared that she had been left at the Gate of Hope – an entrance to the orphanage and home for abandoned babies run by the Infant Jesus Sisters – at the place now known as CHIJMES. Thankfully, some were successful in their search.

Who am I?

As the stories above show, the search for one’s parents implicates something deep, touching on profound questions about one’s identity and place in the universe.

Sometimes, the story is the reverse, where biological parents go in search of children they had put up for adoption. In 2017, the Crime Library Singapore put forward a heartfelt appeal on behalf of a 96-year-old mother Madam Tan, looking for a daughter and son she had put up for adoption due to financial difficulties. According to her son, the elderly woman was “longing to have a look at them before she leaves this world”.

All of these point to a deep moral significance of the biological connection between parents and children. It is also a fundamental human right, affirmed by the CRC.

The wider question that challenges us today is: How can our society help to ensure that this precious bond between parents and children is preserved and protected, as far as possible?