On 15 April 2024, the new Tripartite Guidelines on Flexible Work Arrangement Requests were revealed. This was jointly developed between the tripartite partners – Ministry of Manpower, Singapore National Employers Federation and National Trades Union Congress. The Guidelines come into effect this December.

These latest Guidelines have been in the works for around seven months, since the first meeting of the working group in September 2023.

The Guidelines set out how employees should request for flexible work arrangements (FWAs) and use them, and how employers and supervisors should handle FWA requests.

FWAs are defined as “work arrangements where employers and employees agree to a variation from the standard work arrangement”. These fall within the categories of flexibility in terms of work location (flexi-place), timings (flexi-time) and workload (flexi-load).

In light of Singapore’s possibly record-low total fertility rate (TFR) of 0.97 in 2023, the Government has presented FWAs as a family-friendly workplace practice and “a more sustainable approach to help parents manage both work and caregiving responsibilities” than legislated leave. This is echoed in the Guidelines themselves, which state that FWAs “enable employees to work while juggling family responsibilities such as caregiving”, which will become “increasingly prevalent as our society ages.”

Are these new Guidelines a game-changer in the way we balance work and caregiving responsibilities?

What Do the Guidelines Say?

The Guidelines allow for existing formal and non-formal practices in relation to FWAs to continue, but employees may choose to use the process under the Guidelines if the existing process for requesting FWAs is “absent or lacking”.

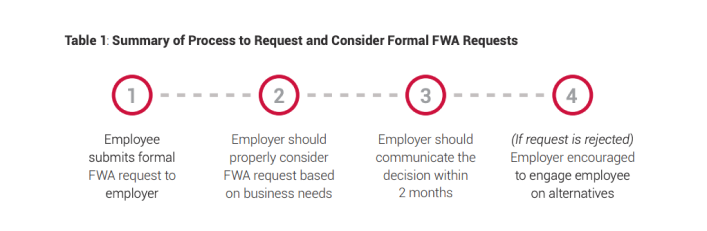

Employees can use the four-step process per the Guidelines.

First, the employee must make a formal FWA request in writing. This should include the date of the request, the FWA requested for (including its expected frequency and duration), reason for the request, and requested start and end dates (if relevant).

Second, the employer must consider the request “properly”. The employer should focus on factors related to the employee’s job, and how the requested FWA may affect the business or the employee’s performance.

Employers can reject FWA requests, but these must be based on “reasonable business grounds”. Examples given in the Guidelines are cost, detriment to productivity or output, or that it is not feasible or practical to accommodate such a request. On the other hand, the Guidelines list examples of some “unreasonable grounds for rejection”:

- “Management does not believe in FWAs.”

- “Supervisor prefers to have direct sight of employee in office so that he/she can see if they are working, even though the employee has consistent satisfactory work performance.”

- “It is the organisation’s tradition or custom to not have FWAs (e.g. staff have always been required to be in office during regular office hours, do not want to start allowing FWAs as other employees may request too.”

Third, the employer must provide a written decision on the request within two months, providing reason(s) for rejection. They are also encouraged to discuss FWA requests in an “open and constructive manner” and come to a mutual agreement on “how best to meet both organisational and employees’ needs” within those two months.

Fourth, employers are encouraged to discuss “alternatives” with the employee if they reject the request.

The Guidelines conclude by encouraging all to foster a workplace culture “based on trust and open communication”, so as to create “more inclusive and productive workplaces, where employees give their best at work and at home, and businesses harness the full potential of our workforce.

As mentioned by the tripartite workgroup behind the Guidelines, the rules cover formal requests for FWAs and the submission and evaluation processes , but do not govern the outcome.

Game-changer, or Not?

So, are these new Guidelines a game-changer?

Probably not, even though they are a step in the right direction.

The Guidelines tip the scale in the balance between work and caregiving responsibilities, but do so only to some extent.

A lot turns on the term “reasonable business grounds”, a wide term which depends so heavily on the context of each individual business.

Although it is theoretically possible to raise a complaint with the Tripartite Alliance for Fair & Progressive Employment Practices (TAFEP) in the event of dispute, how would TAFEP be able to decide whether the reasons given by the employer are legitimate or not from a business perspective?

Indeed, the tripartite workgroup has made clear that it is “the employers’ prerogative” to “decide if (an) FWA for a particular job is viable from a business point of view”.

Thus, looking at the examples listed in the Guidelines of “unreasonable grounds for rejection”, it would seem that only those reasons for rejection of FWA requests that are clearly unreasonable from a business perspective would attract consequences from the authorities.

Responsible Use, Cultural Change are Key

From a realistic and practical perspective, the new Tripartite Guidelines on Flexible Work Arrangement Requests are a positive move because of changing expectations of Singaporean workers.

In a 2023 article, International Monetary Fund (IMF) economists Shujaat Khan and Margaux MacDonald found that most Singaporean workers prefer some degree of remote work, with 73% of Singaporean workers indicating a strong preference for a hybrid work model. This was substantially higher than the global average of 63%. The economists also found that employees and employers here have a higher average desire to work from home relative to almost all other countries globally.

These Guidelines facilitate these expectations by laying down a process of dialogue between employees and employers, so that they can better communicate their respective needs and concerns. Like any human relationship, it is always a two-way street based on mutual respect and understanding.

To maximise the effect of these new Guidelines, both employees and employers should seek to understand and address each other’s needs and concerns.

On the part of employees, they should be responsible in making FWA requests, and ensure that they perform their job diligently. In making their requests, it would help for employees to fairly consider the organisation’s business needs, the relationships with fellow colleagues, and how best they can ensure that all interests can still be met without any negative impact.

On the part of employers, they should understand that employees are an integral part of their organisational resources. Showing respect and protecting staff welfare and needs are important to maintain good morale and ensure long-term sustainability of their business. It would not help employers to entirely reject FWAs and force employees to choose between work and other commitments in life, as this may sour relationships and lead them to seek greener pastures elsewhere in a competitive job market.

Beyond that, a wider cultural change is needed in this balance between work and life, as a country which has been ranked by Instant Offices in 2022 as “the most overworked country”.

Faced with a reality of – in the words of Minister Indranee Rajah – “the twin demographic challenges” of “a persistently low fertility rate and an ageing population”, the need to resolve the tension between work and caregiving responsibilities is a growing necessity. This is because of the potentially shrinking workforce, as well as the growing number of “sandwiched” families who have to juggle caregiving responsibilities towards both the young and old.

To ensure social sustainability, it is high time for us to moderate our (over)commitment to work in our workaholic culture.

To do this, we need to refocus our attention on things which are important, but not necessarily measurable in dollars and cents. These include time with our families, and spending time with (including providing care for) our loved ones, both young and old.