Divorce rings were “having a moment” just a few weeks ago, in yet another way to celebrate divorce in style (and in consumerism). Divorce is now associated with words like “new normal,” “conscious uncoupling,” and “co-parenting” of children – a change from the shame and stigma that used to surround it.

As most of society normalises divorce and seeks to make it easier – how do we tread the line between helping those going through difficult life stages such as their marriage and family falling apart, while recognising the social costs of divorce? What exactly is this social cost anyway?

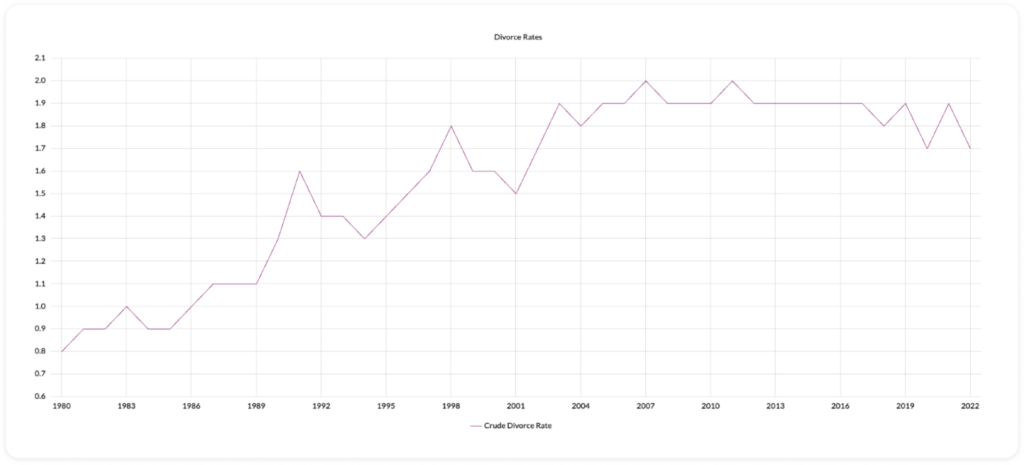

But first, let’s look at Singapore’s marriage and divorce rates.

View the original table at https://tablebuilder.singstat.gov.sg/table/TS/M830202

The crude divorce rate (number of divorces and annulments granted in the year per thousand population) has shown a general upward trend since the Government started tracking this in 1980. It has apparently stabilised since around 2005, and seems to show signs of plateauing, or even a downward trend.

The drop in the number of divorces could possibly be due to fewer marriages, as well as population decline.

If we track the number of marriages that end in divorce over a longer period of time, we see a more realistic picture. From 2013-2017, there were 270 divorces for every 1,000 marriages. From 2018-2022, there were 279 divorces for every 1,000 marriages. There is still a general upward trend of divorce.

The option for couples to divorce by mutual agreement was introduced on 10 January 2022. Previously, the only “fact” of divorce that did not require pinning any blame on either party’s conduct was a 3- or 4-year separation period before the divorce application. Even then, one party had to be named as the Plaintiff, and the other, the Defendant.

Under the new law, if there is mutual agreement, parties can obtain a divorce without designating either as Plaintiff or Defendant. There is no requirement of prior separation, and they do not need to cite any party’s conduct as the reason for the irretrievable breakdown of the marriage. The Bill has been passed, but as at the time of this article, no fixed date has been set for the new law to take effect. This is however a drastic shift from one of the original purposes in the Women’s Charter Bill in 1961, which was to “make it as difficult as possible to contract out of (marriage)“.

Other nations that have introduced various permutations of no-fault divorce have seen an inevitable rise in divorce rates. In the UK, divorce applications soared by as much as 50 per cent in the week after no-fault divorce laws (without the requirement for mutual agreement) came into force.

It is thus likely that when the new law kicks in, we would see a similar increase in divorces (even if they might be more amicable). With divorce rates set to rise, we are asking what the potential cost of this trend would be to Singapore.

The cost of divorce elsewhere

A study conducted 39 years after no-fault divorce reform in Australia showed that “the rise in divorce has thrown a significant and probably unsustainable burden on the public purse in the areas where the Australian (and other western nations) budgets are most vulnerable – namely the issues of aged care, health and youth affairs.”

The researchers write about the cost of single parenthood (often caused by divorce): “… These family breakdowns cost the Australian economy more than $14 billion a year, with each Australian taxpayer paying about $1,100 a year to support families in crisis.”

The figures in a British study were £41.74 billion in 2011; 7 billion Canadian dollars as found in a Canadian study published in 2009; and at least US$112 billion according to a groundbreaking US study on the costs of family breakdown and unmarried parenthood in 2008.

Canada allowed divorces to be granted on a unilateral, no-fault basis after one year of separation from 1968. The United States followed swiftly, with California in 1969 being the first state to allow a spouse to dissolve a marriage for any reason – or no reason at all. From 1960 to 1980, divorce rates in the United States more than doubled. Ronald Reagan later recounted to his son that signing the bill for no-fault divorce in California was one of the worst mistakes of his political career.

There is a wealth of research showing that while divorce generally leaves both partners worse off economically, women tend to experience a sharper decline in household income and a greater poverty risk.

One study explains the financial penalties on divorced families as such:

“People cannot go from one household into two households, with a duplication of housing costs, furnishings and appliances, and other such expenses, without suffering a significant loss of living standards.”

There would then naturally be a financial burden on the state to help divorced households (especially women and children) with lowered incomes, and to mitigate the attendant socio-economic consequences.

Articles and advice from financial institutions and advisors focus not on whether divorce is a financially sound decision, but mentally prepare their readers and clients on how they can best mitigate the inevitable financial costs.

Given all of the above, we should take a hard look at the costs of increased marital breakdowns to Singapore.

Prioritise saving marriages in Singapore

While there are situations where divorce is warranted and even necessary (such as with recalcitrantly abusive spouses), we should be questioning narratives that popularise all divorces and play down its costs. We should make it a priority to minimise unnecessary divorces.

How do we do this? This starts from marriages – including focusing on the right reasons to get married. Some may get carried away by weddings, instead of zooming in on what matters – when two people enter into a new life together, hopefully, forever. One study in the US even found that the length of marriage was inversely associated with the spending on the rings and weddings. Could this be true here too, especially when wedding industry advertisements meet Instagram wedding posts – creating a whole lot of choice and external pressure to have the perfect wedding?

No shade on those who want their perfect “I dos,” of course, only to say that it should not come at the price of a healthy relationship. That takes hard work, commitment, and a whole lot of administration. Helping young couples better navigate the administrative minefield, and free up their minds and hearts to focus on their relationship would help. This is why the new ROM website, combining all the administrative issues for marriage, is helpful. If only they could integrate it with HDB applications.

Conducting local studies on the full economic and social impacts of divorce would be another good place to start. As with all other reforms, we might also do well to take a “wait and see” approach before any further changes to divorce laws. We need to thoroughly assess the impact of the new option for divorce by mutual agreement, and see what robust safeguards can be put in place to ensure that divorce doesn’t become a simple administrative process and becomes an easy fallback for couples who may stand a good chance of staying together through attentive care and life adjustments. Some argue that making divorce “hard” extends the suffering of those in unhappy marriages, but this is where harder questions must be asked, and there are no easy answers.

Marriage is primarily about two people, yet we have seen that there are also social costs when it fails – at the end of the day, we must ask on whom the burden should fall? While there is great sympathy for those having a difficult time during their marriage, there is still a shared responsibility of all of us to minimise the social costs of divorce.

So while we expend resources on mitigating the effects of divorce, perhaps we should also look deeper into changing the mindset that divorces are inevitable, or that marriages should last only as long as both parties are “happy” with each other. Such attitudes towards marriage often fail to consider the most vulnerable parties in a family: the children, who benefit most from healthy and intact marriages. When more couples with children decide to give up without first doing all they can to save the marriage, the children are the ones picking up the pieces for choices they did not make, and society must rally around them.

And so as we continue to have national narratives around marriage and divorce, we should prioritise the right things for marriage – which are centered on, yet go beyond, individual happiness. Are we prepared to pay the price for more divorces, or are we prepared to reconsider what matters in marriages and do the hard work for the next generation?