In a 2021 speech on “New Tribalism and Identity Politics”, then-Finance Minister Lawrence Wong warned against the rise of a “new tribalism” in politics or “identity politics”, citing examples from around the world.

If we are not careful, he said, the “culture wars that began in the West” – involving things like debates over abortion, voting, “woke culture”, vaccinations and mask-wearing – can easily take root here. These go beyond the divides of race and religion which are familiar to Singaporeans. Former President Halimah Yacob echoed these thoughts in a 2023 speech, saying: “Identity politics is on the rise and is a real threat to society.”

Across the world today, we see polarisation and division within many different societies, including in Singapore. Such fractious and divisive identity politics can certainly damage social harmony and the unity of the country in the long run.

Is identity politics always bad?

Two Kinds of Identity Politics

According to social psychologist and author Professor Jonathan Haidt, there are two kinds of identity politics.

One kind of identity politics is “common humanity” identity politics. It emphasises an overarching common humanity, by “drawing a larger circle around the group,” highlighting what is common. It then argues that fellow human beings should not be denied dignity and rights just because they belong to a particular group, while not demonising other groups.

A classic example of such language was found in Martin Luther King Jr’s famous “I Have A Dream” speech, advocating for the equal rights of black people to white people. He imagined a country where people would be equal regardless of race and religion: “When we let freedom ring, when we let it ring from every tenement and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old spiritual, ‘Free at last, free at last. Thank God Almighty, we are free at last.’”

The other kind is “common enemy” identity politics. This seeks to amplify the human tendency towards “us versus them” tribalism, and binds people together in a shared hatred of a group that serves as the unifying common enemy. It essentially identifies a particular group or groups as the “bad people” that the “good people” must unite against.

Such “common enemy” identity politics includes language blaming a particular group of people for injustices and wrongdoing in the world. For example, feminist author Germaine Greer criticised males in her book The Whole Woman: “To be male is to be a kind of idiot savant, full of queer obsessions about fetishistic activities and fantasy goals, single-minded in pursuit of arbitrary objectives, doomed to competition and injustice not merely towards females, but towards children, animals and other men.”

It gets dangerous for society when such language is used to demonise fellow citizens whom one disagrees with. Classifying people into oppressors and victims just because of racial / religious / sexual / gender markers can incite discrimination and even violence.

What Are Some Examples from Singapore?

Singapore became independent against the backdrop of communal politics and in the wake of racial riots.

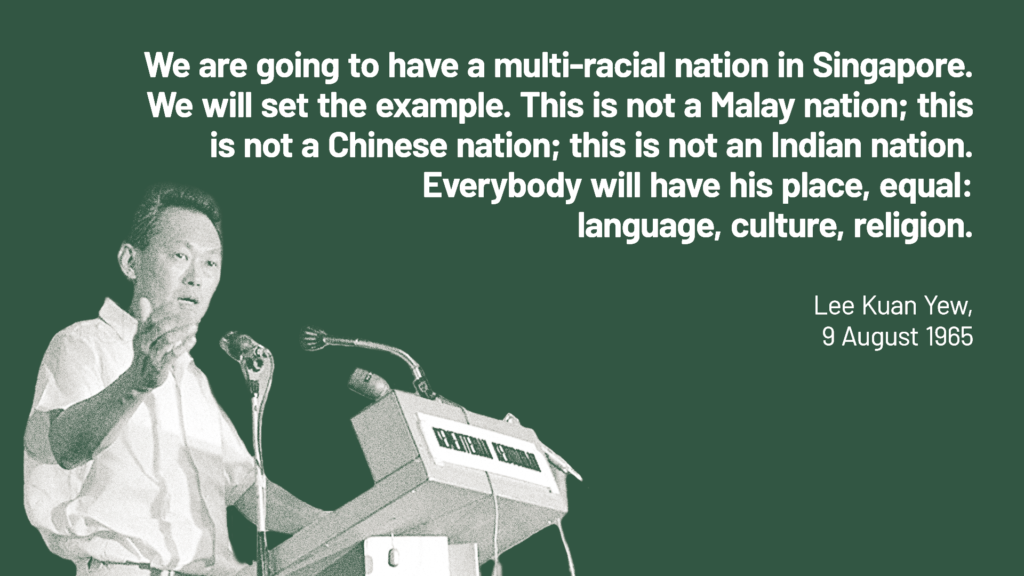

Rejecting the kind of polarisation and division that characterised the tumultuous years of merger with Malaysia, Singapore was founded on the basis that it would be a multi-racial and multi-religious society.

Founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew reflected a “common humanity” approach towards identity, in his famous post-Independence speech where he declared: “We are going to have a multi-racial nation in Singapore. We will set the example. This is not a Malay nation; this is not a Chinese nation; this is not an Indian nation. Everybody will have his place: equal; language, culture, religion.”

Singapore’s laws thus take a strict stance against those who make offensive remarks on the basis of race or religion. Law and Home Affairs Minister K. Shanmugam said that “racial and religious harmony” is part of the “fundamental assurance” that one gets in Singapore.

One example of “common enemy” kind of language was in 2017, when an Islamic religious leader – Imam Nalla Mohamed Abdul Jameel – uttered the phrase “Grant us help against the Jews and the Christians” during a Friday prayer at a mosque. It was a phrase which the Ministry of Home Affairs said could also “be interpreted as asking God to grant Muslims victory over Jews and Christians”. Imam Nalla was fined by the Singapore courts for making offensive remarks against Christians and Jews.

Another incident was in 2019, when YouTuber Preeti Nair and her brother Subhas Nair stirred controversy for putting up a rap video which contained the lyrics “Chinese people always out there f***ing it up.” This was done in response to an e-payment advertisement by Nets and Havas which featured “brownface”. Minister K. Shanmugam criticised the video for crossing the line: “When you use four-letter words, vulgar language, attack another race, put it out in public, we have to draw the line and say ‘not acceptable’.”

The police gave the Nair siblings a 24-month conditional warning for the video.

More recently in 2022, a high-profile incident took place involving former polytechnic lecturer Tan Boon Lee. He was caught on camera confronting a mixed-race couple (Dave Parkash and Jacqueline Ho), saying “such a disgrace, Indian man with a Chinese girl”. He accused the man of “preying on a Chinese girl”. In reality, Parkash is half-Indian and half-Filipino, while Ho is half-Thai and half-Singaporean Chinese. Tan was sentenced to five weeks’ jail and a $6,000 fine for wounding an individual’s racial feelings and possessing obscene films respectively.

The examples above involved instances of “common enemy” language, which targeted people based on religion and race respectively. Such language reflects an “us versus them” attitude, identifying particular racial or religious groups as the “enemy” who are to be blamed for alleged injustices or defeated.

Emphasising Our Common Humanity

“Common enemy” identity politics is rising in places around the world, but it does not have to be so.

Things do not have to be “us versus them”, or a kind of zero-sum “I win, you lose” kind of situation. Jonathan Haidt recommends instead that we should seek to resolve problems in a spirit of “we’re all in this together”.

For example, we can begin by recognising and emphasising our common national identity (as Singaporeans) or that “we’re all human beings”. This includes recognising that people do make mistakes from time to time, and giving them opportunities to improve their behaviour.

This was exemplified in the case of Imam Nalla. Following his remarks, he apologised to various religious leaders (including Christian and Jewish leaders), who accepted his apology. On the day he attended court, he was accompanied by religious leaders of different faiths.

The reconciliatory actions of both the imam and the other religious leaders achieved and exemplified something remarkable. Not only was it the opposite of an “us versus them” attitude, it reflects a common effort to promote unity and restore the hard-earned social harmony.

Instead of narrowing the circle of trust, the religious groups had drawn a larger circle in an attitude of forgiveness and respect.

As internal and external factors risk polarising and dividing society in the 21st century, we certainly have much to gain by doing likewise and emphasising our common humanity instead of descending into tribalism and conflict.