“Gay marriage is wrong.”

“The definition of marriage should remain as the legal union between a man and a woman.”

If people were asked whether they agree or disagree with these statements, would they answer differently?

In August this year, the Institute of Policy Studies (IPS) published a paper titled “Moral Attitudes in Flux: Comparing Trends Across Religions in Singapore” (Working Paper 66). In that paper, the research centre under the National University of Singapore assessed ten moral statements. Four out of the ten statements zeroed in on same-sex behaviour or choices such as sex, surrogacy, and marriage.

The IPS researchers concluded that Singapore residents’ views on gay sex and marriage “liberalised significantly” over the past decade, so that just over half of the population disapproved in 2024.

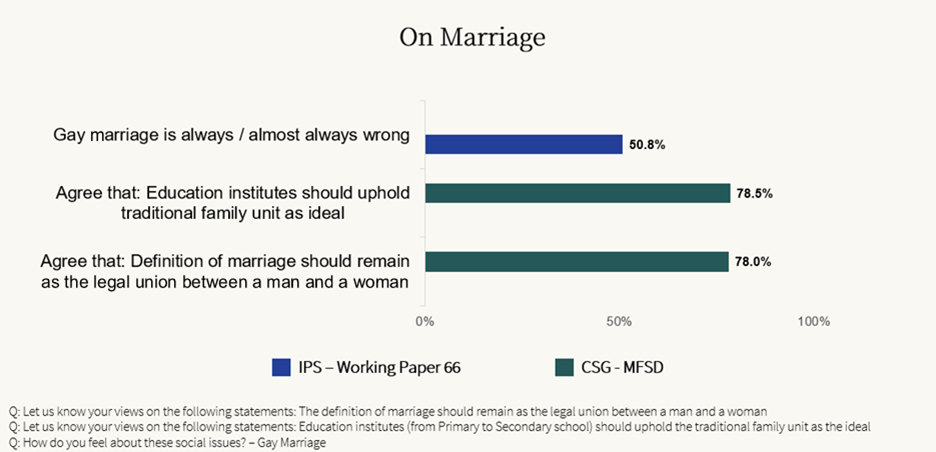

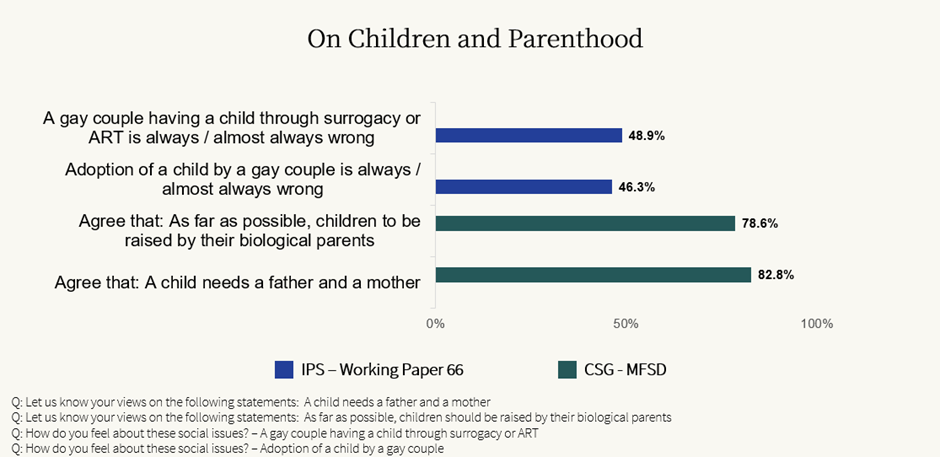

These findings are interesting, when compared with Cultivate SG’s 2024 “Marriage, Family and Social Discourse” (MFSD) survey. While our MFSD survey did not share similar levels of focus on same-sex behaviours or choices, we found that almost 8 in 10 respondents supported the current legal definition of marriage as between a man and a woman.

IPS surveyed 4,000 Singapore residents using a household survey design. Our online survey covered 2,000 Singapore citizens and permanent residents. Both were general population surveys.

Are these findings contradictory?

Topline findings at a glance

At first glance, there seems to be a significant difference in attitudes towards same-sex marriage between the two surveys.

While our survey found overwhelming support for the definition of marriage as a man-woman union and the traditional family unit (around 78%), the IPS survey found that only a small majority (around 50.8%) considered “gay marriage” to be “always wrong” or “almost always wrong”.

Similarly, around 8 in 10 respondents to our survey emphasised the need of children for their father and mother, and to be raised by their biological parents. By contrast, less than half of respondents to the IPS survey disapproved of gay adoption or gay couples having children through surrogacy or assisted reproductive technology (ART).

Why are the survey results so different?

One likely explanation for the differences between the two surveys lies in the way that the questions were framed.

People tend to be more willing to say they “support” certain societal norms, especially when these are already established in society. By contrast, they may be more hesitant to agree that something is morally “wrong”, particularly when it touches on sensitive or controversial issues.

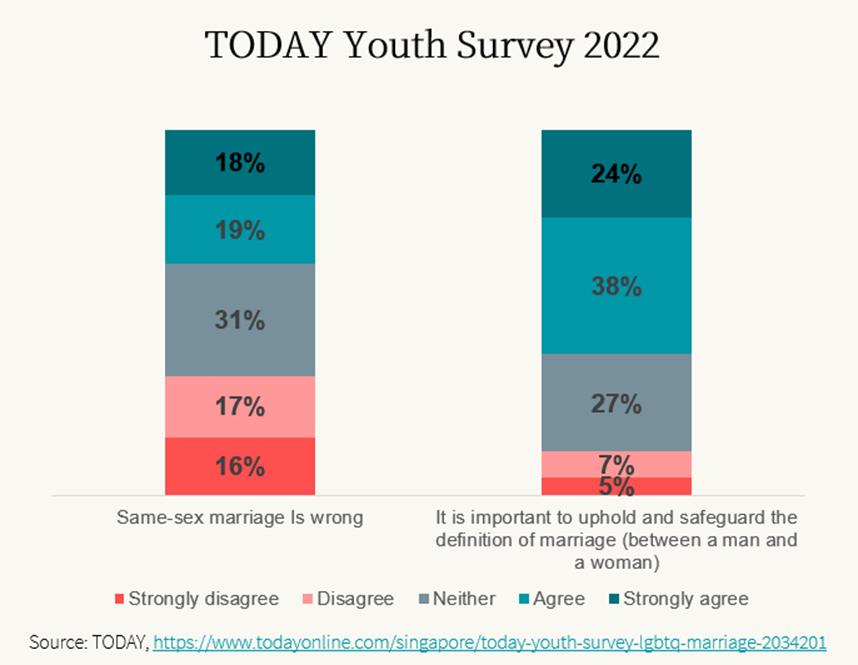

This may have explained an interesting dissonance in a 2022 survey by TODAY of youths (between 18 to 35 years-old). While respondents were “split” over whether same-sex marriage is “wrong”, more than 6 in 10 felt that it was “important to uphold and safeguard the definition of marriage (between a man and a woman)”, with only about 12% disagreeing.

Furthermore, the IPS survey asked questions based on the extent to which they felt certain actions were “wrong”, with five options on a single scale ranging from “not wrong at all” to “always wrong”. By contrast, our MFSD survey measured whether respondents agreed, disagreed or did not have a view on a statement about certain societal norms.

Questions for Comparison

| Topic | Cultivate SG MFSD | IPS Survey | |

| Definition of Marriage | Question | “The definition of marriage should remain as the legal union between a man and a woman” | “Gay marriage is ____” |

| Options | 1. Strongly agree 2. Agree 3. No strong opinion / haven’t thought about it 4. Disagree 5. Strongly disagree | 1. Always wrong 2. Almost always wrong 3. Only wrong sometimes 4. Not wrong most of the time 5. Not wrong at all | |

| Results | Overall: 78.0% Agree/Strongly Agree; 18-34: >66.8% Agree/Strongly Agree | Overall: 50.8% Agree (Always/Almost always wrong); 18-35: 35.3% Agree (Always/Almost always wrong) |

Other methodological differences

Differences in methodologies will also affect results.

Our MFSD survey sampled 2,000 respondents and was done in English online through a market research panel. As a result, it tended to reach people who were more digitally connected, and there may be some difficulty understanding and responding to the survey if a respondent’s command of English is weaker.

While respondent reach was calibrated and results of our survey were weighed to mirror the prevailing demographics of Singapore’s resident population, our sample was limited to the existing pool which signed up to be on the research panel.

On the other hand, the IPS survey had 4,000 respondents. It comprised those from a list of 6,000 randomly generated residential household addresses obtained from the Department of Statistics (DoS) and a booster sample of approximately 1,000 Malay and Indian minority-race respondents for better representation and enable fine-grain comparisons across responses. The surveys were then conducted offline, with surveyors visiting respondents, briefing and administering the survey by allowing respondents to self-complete the survey using a provided tablet (e.g. iPad, Galaxy Tab). If the respondent needed help, the surveyors would step in accordingly.

As the IPS acknowledged in its paper, there may be “social desirability bias” arising from the face-to-face method, where respondents answer the survey in a way that would be viewed “more favourably” to other people. However, the IPS said it “partially resolved” this through its use of the tablet, giving respondents some privacy to answer the questions on their own while the surveyor is present.

There could be various other reasons for the differing findings between the two surveys. Thus, it will be most beneficial for readers to personally explore both surveys to gain insight concerning the nuance and tension of various societal norms and perspectives.

Getting a nuanced view

Taking both surveys together gives us a fuller picture of where Singaporeans stand on values. It seems Singaporeans may be less willing to appear or be “judgmental” on sexual matters, even though many still value marriage (as the union between a man and a woman) and the traditional family unit.

Despite some differences in results across the two surveys, there are converging points. There is a general trend of liberalisation, with it being the strongest among younger age groups. However, fidelity in marriage is still strongly emphasised, and a person’s background is a strong predictor of a more conservative outlook.

Amidst these pluralistic and differing moral attitudes, perhaps the more important task is to examine the reasons behind various social norms surrounding marriage, family, adoption, fertility treatments and surrogacy. Unfortunately, the welfare of children is something that is often left out of the discussion, including their need for a father and a mother.

Marriage and culture are part of a wider ecosystem that helps protect the welfare of children (and their families), an ecosystem that includes seemingly unrelated ones like workplace rules, media guidelines and education. A more holistic perspective on these matters will be helpful moving forward.

(Correction note: The article has been amended to remove a wrong statement that IPS had used a mix of online and in-person surveys.)