Prior to assuming his role as Singapore’s fourth Prime Minister (PM), then-Deputy Prime Minister Lawrence Wong said that his Government would be “prepared to relook everything”, though it would not “slay a sacred cow for the sake of doing so”.

Delivering his first-ever National Day Rally, PM Wong did not disappoint in this regard.

Among the much-needed refresh to policies were those related to family, where he announced that the 4-week Government Paid Paternity Leave (GPPL) would be made mandatory from April next year. This is a change from the current policy where only 2 weeks are mandatory, while the other 2 weeks are voluntary.

However, perhaps the most significant announcement was the ten additional weeks of Shared Parental Leave, on top of the existing paternity and maternity leave entitlements of 4 and 16 weeks respectively for eligible parents.

Need to Improve Take-up Rate

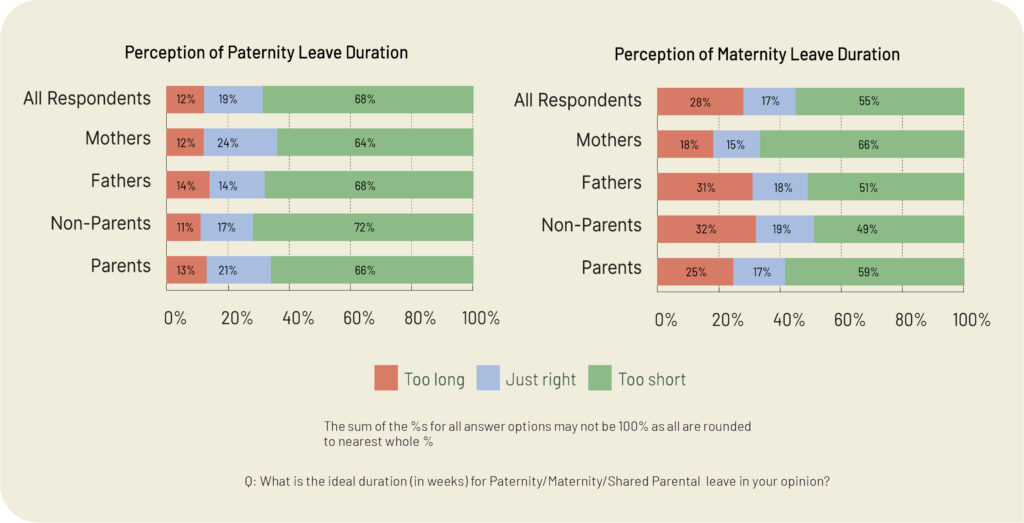

These changes are likely to be welcomed by society, as can be seen from the results of a survey on parenthood and work which we published before the Rally. 68% of respondents had said that the existing length of paternity leave was too short, while 55% said the same for maternity leave.

Conducted by Milieu Insight, our survey covered 1,000 Singaporeans, including 600 parents.

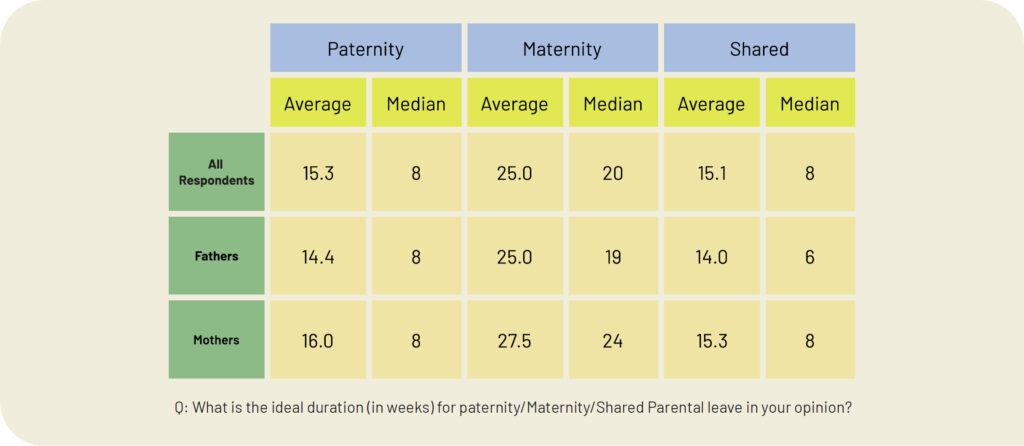

The latest announcements even exceed what our survey found in terms of the ideal parental leave duration. Among respondents, the median ideal maternity leave duration was 20 weeks, more than double the median ideal paternity leave duration (8 weeks).

At the same time, there are strong hints of deeper challenges ahead. There is a risk that, despite the increase, such parental leave may not by fully taken up in practice. Indeed, signs of this can already be seen from the fact that only slightly more than 1 in 2 new fathers took paternity leave in 2022.

Such challenges to take-up rates arise from various pressures including societal attitudes on parenthood, and work commitments.

Societal Perceptions of Fathers and Mothers

As PM Wong observed during his speech, there is a societal attitude among some that fathers should be the “exclusive breadwinners” and mothers the “main caregivers”.

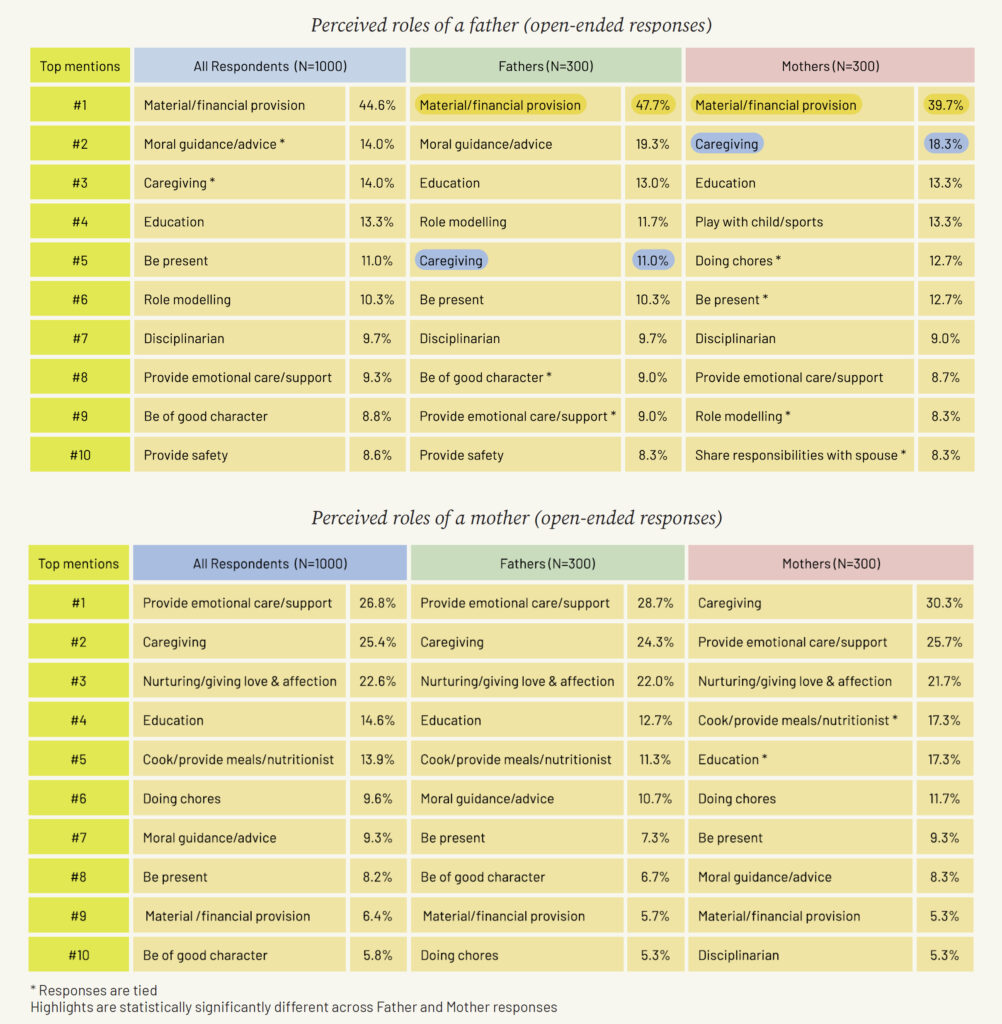

Our survey found, in open-ended responses to perceived roles of fathers and mothers, that “material and financial provision” was the top-mentioned perceived role of a father (44.6%). By contrast, care-oriented roles dominated as the most common perceived roles of a mother.

Interestingly, fewer mothers (39.7%) than fathers (47.7%) tended to see “material and financial provision” as a father’s role. Mothers also regarded “caregiving” as a role for fathers (18.3%) more commonly than fathers do (11.0%).

These differences in perceptions suggest that mothers would prefer fathers to take up more caregiving roles at home.

These perceptions on the roles of respective parents played out quite predictably in practice, where mothers were consistently the main caregivers throughout a typical week. In the mornings and afternoons on weekdays, mothers were most commonly the main caregivers (44%), followed by institutionalised childcare or education (21%) and then grandparents (15%). Only 5% of fathers were only the main caregivers, lower than domestic helpers (8%).

On weeknights and weekends, the figure for mothers increased to around two-thirds (around a 22% increase), showing that working mothers were still typically shouldering more caregiving tasks outside of working hours. On the other hand, the proportion of fathers as main caregivers increased to 12% on weeknights, and around 17% on weekends.

Challenge of Work Commitments

The second set of challenges in take-up rates of parental leave arises from work commitments, which also implicitly embody certain gendered expectations.

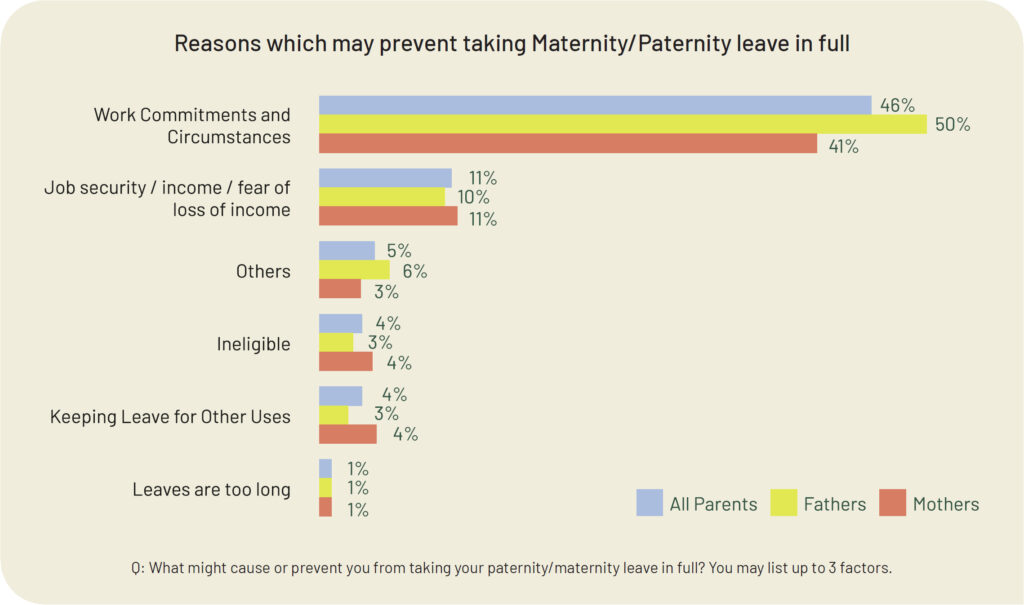

When parents were asked what might cause or prevent them from taking paternity or maternity leave in full, almost 1 in 2 (46%) indicated work commitments and work circumstances as such possible barriers.

This is consistent with findings released by the Ministry of Digital Development and Information, which found that work commitments were the key reason why parents could not be the main caregiver for their babies.

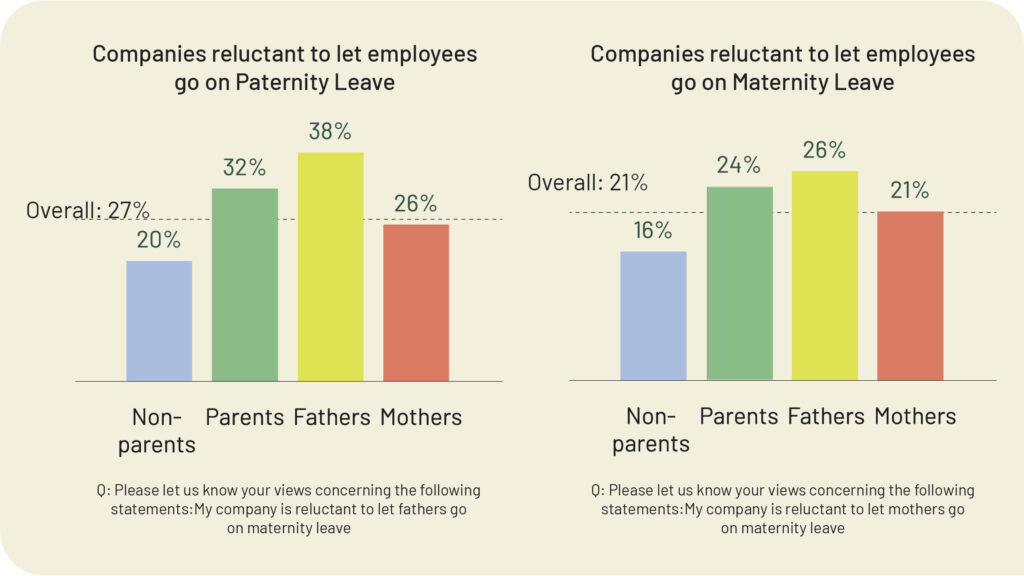

Among our respondents, at least 1 in 5 expressed that their companies have been reluctant to let employees go on their respective parental leave (21% for maternity leave; 27% for paternity leave). Higher numbers of fathers reported such reluctance, where 38% said their companies were reluctant to let fathers go on paternity leave.

A significant amount of pressure against taking parental leave may also stem from unhappiness among fellow colleagues, where around 1 in 3 respondents reported feeling frustrated when they were required to cover work for a colleague on parental leave. Such frustrations may often be due to – to quote one of the open-ended responses we received – a lack of “compensation or recognition of the work” that was done when providing cover.

To be fair, employers and businesses have legitimate concerns about managing manpower gaps when their employees are away for an extended period, as PM Wong had noted in his speech. With the planned increases in parental leave, employers will be faced with added challenges in managing the morale and sentiments of employees, apart from the potential impact on their work due to the mandated employee absence.

Temporary Hires: A Possible Solution?

A possible solution to the manpower gap may be found in the practice of hiring temporary staff to cover employees who go on paternity or maternity leave, sometimes known as “maternity covers” or “paternity covers”. With the introduction of mandatory 4-week GPPL and 10 weeks of Shared Parental Leave, there is room to grow the industry of temporary hires to cover employees who go on parental leave.

Our survey contained an optional open-ended question on this topic, which received relatively more positive feedback on temporary hires compared to a situation if an employee personally covered for a colleague on parental leave.

Although the feedback on such temporary hires was still mixed, the responses suggested that it is important to obtain temporary staff with suitable skill and competence, positive attitude, and for companies to ensure proper management and handover to and from such staff.

Beyond that, there may be a need for the Government to consider ways to support smaller businesses in filling these manpower gaps while employees go on parental leave, and to ensure suitable protections for temporary staff.

Valuing Men and Women, in Domestic and Public Life

The policy announcements are a significant step forward in promoting shared parental responsibility in the upbringing of children, but policy alone can only go so far. To build a Singapore that is truly “made for families”, we need a wider shift in our hearts and minds.

Certainly, some differences between fathers and mothers are simply natural and physiological, such as the need for mothers to recuperate physically from childbirth and to breastfeed newborns. At the same time, we should all recognise that both parents are unique and complementary, bringing their respective gifts and contributions to the family.

Just as we have grown to value the involvement of women in the workplace and other aspects of public life, we should likewise value and encourage the involvement of men in domestic and family life. Even as much of family life is deeply personal and private, it should not be any less valuable to society, since family is its foundational building block.