Singapore has been struggling with declining fertility rates ever since 1977, and our total fertility rate (TFR) hit a record low of 0.97 in 2023.

As part of the Government’s efforts to address the problem, Prime Minister Lawrence Wong announced a new Large Families Scheme to support married couples who have, or aspire to have, three or more children in this year’s Budget. It involves various cash grants to support each third and subsequent child, to cover education, healthcare and other expenses.

Now comes the big question: Will these new measures, as well as recent increments to parental leave and more, be effective in raising Singapore’s birth rates?

Importance of Values in Shaping Fertility

Government spending on marriage and parenthood initiatives will increase to $7 billion in 2026, more than ten times the amount of $500 million spent in 2001. However, as one Civil Service College researcher put it bluntly: “Despite these efforts, Singapore’s TFR continues to decline.”

Demographer Jennifer D. Sciubba, author of 8 Billion and Counting: How Sex, Death, and Migration Shape Our World, noted that while government policies have been effective in lowering TFR around the world, they have not seen success with policies in the other direction – to raise fertility rates – despite large amounts of spending.

Singapore was one of the countries covered in her studies – and unfortunately, our experience proves her point.

Part of the reason may be found in the Second Demographic Transition (SDT) theory, developed by demographers Ron Lesthaeghe and Dirk van de Kaa in 1986. They theorise that values are more important than material resources in affecting fertility rates in developed countries.

Additionally, as populations become wealthier and more educated, they focus less on survival, security and solidarity, shifting their emphasis towards individual self-realisation, recognition, grassroots democracy, expressive work, and educational values.

Minister Indranee Rajah has acknowledged the impact of these trends on Singapore, as part of “a global phenomenon where individual priorities and societal norms have shifted”.

What Kinds of Values?

Our engagements with parents of large families have suggested an underlying comprehensive value system that prioritises children, relationships, developing a sense of responsibility, as well as thrift and financial prudence.

As Mariam Alias, a mother of 7 (and grandmother of 15) put it during our “Unfiltered” conference:

Whether it’s this economy or the 10-years-ago economy or whatever economy you want to talk about, it’s about you… You need to know how to space out your finances, and not want to be overly wanting to do all kinds of things when your finances are that limited. The kids can still grow up with a certain kind of limited finances, but happy, that’s what’s important: happy and moving on life, doing things that are good for them, and you don’t have to splurge on tuition and on ballet dancing, on piano or whatever, that’s maybe not really necessary. So they learn to be frugal at a very young age because you teach them how to move life, and not to spend and do whatever they want to with money and things like that. I’ll still have seven [children].

(Emphasis added)

James, a father of 4 shared similar thoughts at our Commune event last year, emphasising the “different ways of looking at life, having different perspectives of what is truly important, and what is the purpose and meaning of life. We’re rich in different ways.”

Another mother of 7 shared at our “Unfiltered” conference that hers was not a “planned family”, but “it comes as and when it wants, and I accept in that manner”. Her attitude was to “live to the stage where we can afford. We shouldn’t go beyond, then we will not hurt ourselves because of our lavishness whatsoever.” She raised her children at a time when the Government was not offering as much support as it is doing now, but nevertheless believed that one should “be happy with whatever you get, appreciate whatever you have.”

A common thread through their considerations about having children are ultimately not about dollars-and-cents, but about the value and meaning that comes from having children and building families. They see the intrinsic worth and potential of children, and have a deep sense of optimism and hope for the future.

Still “Stop At Two”?

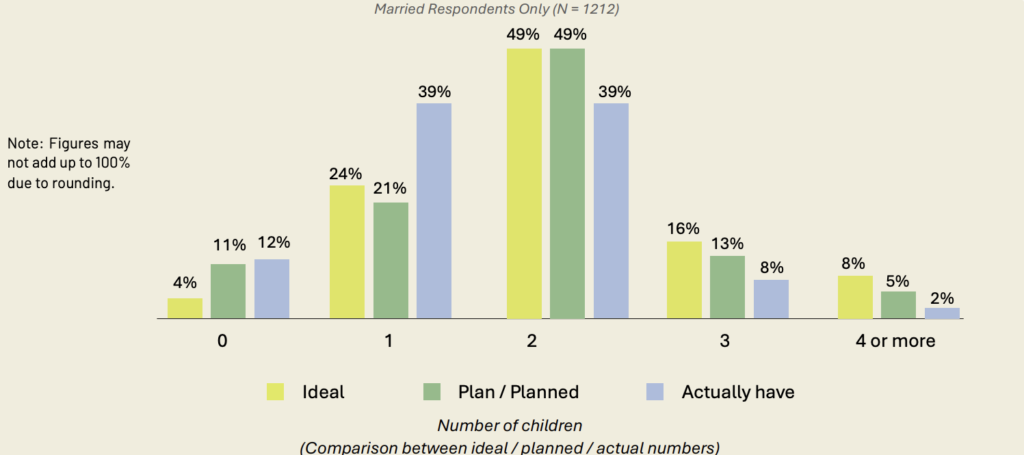

Reflecting the (excessive) success of the “Stop At Two” campaign of the 1970s, Singaporeans typically say that their ideal number of children is two. There are also others who wish to have fewer or no children.

On the other hand, there are some strong negative sentiments and stigma in Singapore towards large families. One particular family had been covered by the Straits Times in April 2022, “Feeding 8 kids on $300 a week: How big families cope in a time of rising costs”.

A Reddit thread discussing the article had significant negative comments, accusing the parents of being “irresponsible” or engaging in “abuse” for having eight children:

These negative sentiments may reflect the long tail of attitudes ingrained into Singapore culture by the “Stop At Two” campaign (and the slogan “the more you have, the less they get”), with the Health Minister in 1972 calling it “anti-social” to have four or more children (as we cited in our first article).

These sentiments also embody the kind of economic pragmatism of the “Have three, or more if you can afford it” campaign from 1987 onwards, based on the idea that “those who cannot really afford to have a large family should keep their family small”.

An increase in such attitudes could lead to a self-reinforcing and self-fulfilling vicious “low fertility trap”, a situation where low fertility and negative attitudes towards children or larger families could reinforce even lower fertility, leading to a downward spiral. Singapore’s stubborn downward TFR trend suggests that we may already be in such a “low fertility trap”.

No Getting Out of This “Low Fertility Trap”?

Is there a way forward? How should we progress?

Societal values shape fertility rates, particularly those relating to marriage, family and children, and also those involving notions of success, attitudes towards parenting and more. Society also needs to move away from measuring childbearing and childrearing according to resource efficiency and affordability, which are reductionist in nature. While it may take time, these values can also be shaped and strengthened.

Furthermore, as our 2024 “Marriage, Family and Social Discourse” survey shows, about of quarter of married couples (total of 24%) say that 3, 4 or more children is their ideal number of children, and those who actually have such numbers are even fewer (8% of those surveyed actually have 3 children, while 2% actually have 4 or more children).

This suggests that there are families in Singapore who could possibly have more children and realise their ideal family size, if the circumstances are right. Support from the Government might be helpful for this group.

However, we think that support can be more systemic and structural in nature, to empower families or lower barriers to enable them to provide for themselves what they naturally would.

So stay tuned for our final article, where we share our thoughts on how large families may be better supported in their journeys!